Today, Rizzoli is releasing a new monograph on the Japanese fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto (YAMAMOTO & YOHJI, Rizzoli, $115). It is a road well-travelled, as there is already a slew of books on Yamamoto – from the collectable Talking to Myself to the forgettable “best hits” pamphlets by the publishers Taschen and Assouline.

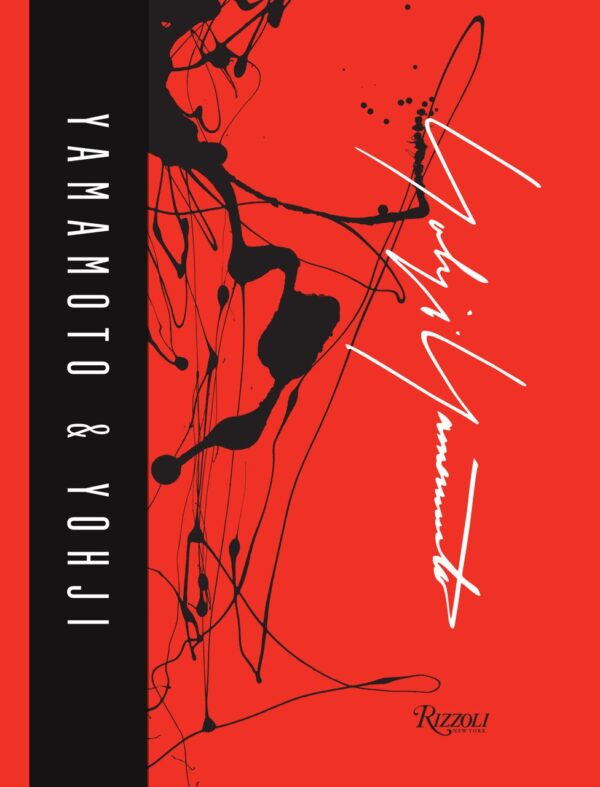

The new volume contains 600 photographs and contributions by long-time Yamamoto’s famous friends, including the French actress Charlotte Rampling and the German filmmaker Wim Wenders. It is a hefty, cloth-bound tome, its 448 pages printed on thick matte paper, as it should be, since once cannot imagine anything glossy (read, vulgar) in the Yamamoto world. The cover is red and black, the two signature Yamamoto colors.

The book provides a comprehensive worldview of Yamamoto’s work. It is organized into four chapters – Philosophy, which gives insight into the designer’s ethos, Biography & Brands, which showcases Yamamoto’s prolific career, A Different Way of Communication, a history of Yamamoto’s shows, and Crossing Fields, which is about Yamamoto’s work outside the catwalk.

Yamamoto & Yohji was put together by two long-term Yamamoto collaborators, Coralie Gauthier, who for years was Yamamoto’s PR (a term that does nothing to describe her importance) has built most of the content, and Paul Boudens, the Belgian graphic designer whom you might know as the mastermind behind A Magazine, designed the book.

The pair, given carte blanche by Yamamoto himself, worked closely together for a year on shaping the monograph. “The two main books, Talking To Myself and the autobiography My Dear Bomb are mainly about the man and his philosophy, not about his collaborations and productions,” Gauthier said. “I felt that it was time to create an anthology of his creative collaboration in theater, dance, music graphic design, architecture, etc.”

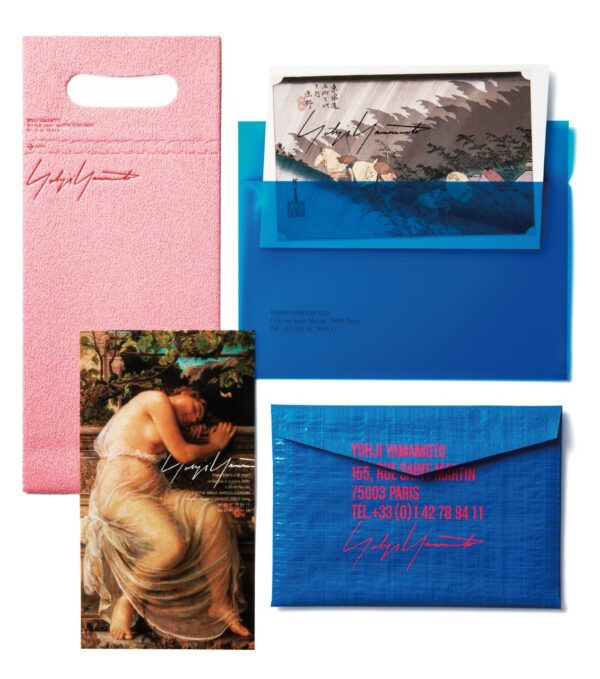

Boudens, who has previously worked with Yamamoto on show invitations, mailers, the issue of A Magazine that was curated by Yamamoto, and My Dear Bomb, was a fitting candidate. “We studied the previous books thoroughly and saw what worked or didn’t. You don’t want to design something inferior, so the pressure was definitely on. I like to think we did a good job, respecting Yohji’s œuvre but still infusing our own style, content-wise for Coralie, design-wise for me. We share the same esthetic anyway; a search for timelessness, attention to detail and tactility,” Boudens said.

The book begins with some images that are well familiar to those who have followed Yamamoto’s career. (Not to worry, it also contains plenty of visual material that has rarely been seen before.) These are interspersed with some quotes by the master. “I always sing the same song, only with new arrangements,” is one that perfectly describes Yamamoto’s philosophy of subtle changes, deep contemplation, and a body of work that possesses a core.

And, of course, there are thoughts on black, which I suspect few in the audience of this publication need validation of, but here is one anyway, “Black is the most profound and under-appreciated color. It’s a second skin for me. When I was very young, I made black t-shirts. At the time, Japans was having an economic boom. Social success had become an obsession, and the whole country was vibrating under a shower of colors. My black was a sign of protest, the opportunity to be a shadow in a boring system that I was rejecting.”

The question of clothing as a marker of identity permeates Yamamoto’s work. You are what you wear. “My message was very simple: let’s be outside of this. Let’s be far from our suits and ties. Let’s be far from businessmen. Let’s be vagabonds,” is how the designer explains the ethos of his menswear.

The book continues to the history of Yamamoto’s company and the overview of various lines and collaborations, from Dr. Martens to Hermes. It is a sizeable section that reminds us just how much the man has done.

The third section is devoted to Yamamoto’s runway shows. It is a straightforward timeline, but you may be disappointed by the images, since most collections are represented by a single tiny photo. That is too bad, considering the dearth of images in the pre-digital era that could have been used here, thought it probably would have made the book a two-tome affair.

On the flip side, there is a neat subsection devoted to Yamamoto’s show invitations, and if you’ve ever been to a show you will know that invitations are a form of art all onto its own. My favorite of these is from the F/W 2013 women’s collection – black yarn had to be unspooled in order to see the show’s address engraved on the wooden base beneath.

The runway timeline is followed by the work of Yamamoto’s collaborators – a veritable procession of photographers, art directors, graphic designers. Yamamoto devotees will know most of them – Paolo Roversi, Nick Knight, Max Vadukul, Craig McDean, M/M Paris, and Marc Ascoli, among others.

The last section of the book goes through the other parts of Yamamoto’s venerable career. There is a section that is devoted to his exhibits. The most comprehensive of these were in Florence and at the Design Museum of Holon in Tel-Aviv.

Last but not least, the book provides the reader with a tour of Yamamoto’s boutiques around the world. This is important because it was the Japanese that have revolutionized retail in the 80s and 90s. The way many boutiques look today, with their gallery-like spaces and presentation, owe a big debt to Yamamoto and other Japanese designers. Sadly, some of Yamamoto’s boutiques, especially the one on Grand Street in New York (sadly, there is no mention of it in the book) and the one in Antwerp, have been shuttered.

The day the Yamamoto boutique in SoHo closed was a day of mourning for many a fan; doubly so when Alexander Wang took over the space. It was also a sign of the times – the rise of streetwear, the loss of appreciation for quality, and the general disregard for the genius of creation in favor of branding. Hopefully, this monograph will serve as a reminder of the rich history that one of the most talented fashion designers has bequeathed to us.

All images are from YAMAMOTO & YOHJI, Rizzoli New York, 2014