Gary Schneider arrived in New York City from Cape Town in 1976, landing a job doing technical work for an avant garde theater in Soho. Through his partner, he met artist photographer Peter Hujar with whom he had an immediate rapport as he was interested in photography and printing. Hujar secured Schneider a job at a printers, and in the process becoming a close friend, protége, assistant and occasional subject for Hujar’s lens. Eventually, Schneider also printer Hujar’s photographs. Their relationship is now commemorated in a new book Peter Hujar Behind The Camera And In The Darkroom (BookCrave. $50, out now).

1976 was also the year Hujar’s seminal book “Portraits In Life And Death” was released. Now considered a must have for any serious photography connoisseur, the portraits are a who’s who of New York City’s downtown glitterati: writers, actors, filmmakers, and artists, all sensitively captured in various shades of black and white. But it is the hauntingly beautiful images of the catacombs of Palermo, the portraits of death, is where Hujar’s talent with light and shadow comes into focus.

Schneider discusses Hujar’s remarkable attention to detail, their trial and error, and experimentation with darkroom techniques. Less concerned with simply creating a beautiful picture (although his photography is beautiful) Hujar wanted to control the way information is revealed to the viewer. His work from the 1960s had more contrast, a stark immediacy akin to crime photographer Weegee. But by the Seventies, his obsession with shading, tonality, depth and detail produced pictures with a subtle, yet highly controlled narrative. In one of his most famous images, “Boys In Car, Halloween, 1978”, Schneider shows over six pages (a different version of the same image is printed on each page) how Hujar manipulated the negative in order to highlight or subdue what the camera initially captured. It is a delightful revelation and a peek into the mind of the artist.

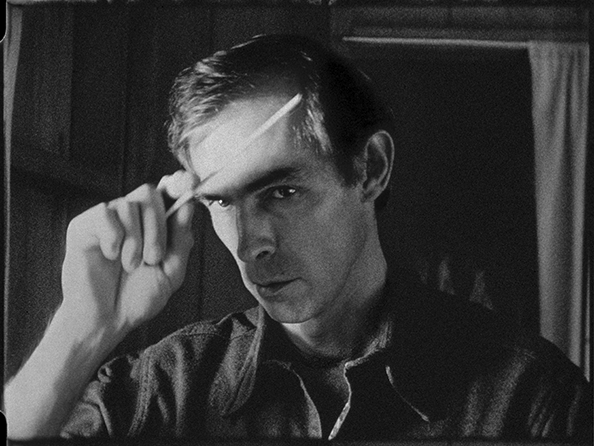

The centerpiece of the book are seven rolls of Schneider posing for Hujar’s Rolleiflex where he intimately talks us through the experience. Although Schneider’s words are expressed with a matter of fact tone, it is a touching recounting of the relationship between artist and muse, albeit fleeting. Hujar does not direct him throughout the sitting but follows him with his hand held camera. It becomes a dance. Slow and awkward initially, but in sync after a few rolls. Schneider describes the gamut of his feelings from anxiousness, embarrassment to sexual arousal, and how he wants to please Hujar, looking at him for signs of approval so that he may get the picture he is looking for. An image from the final roll is selected and graces the cover of the book. Schneider, his legs thrown over his head (he practiced yoga) looks passively at Hujar but with an air of mild uncertainty. It is this uncertainty which lends the picture complexity. It is a celebration of form but not at the sake of sacrificing Schneider’s emotional interiority.

The book concludes with night photographs of cruisers in Stuyvesant Park, in the Summer of 1981. Schneider describes the fun and illicit thrill both he and Hujar experienced that evening. The pictures show New York’s era of sexual permissiveness, where homosexual men found each other in public spaces, right before it would all end with gentrification and AIDS. Hujar would be one of the many casualties of the AIDS epidemic which devastated the artistic and creative communities of its many talents. Schneider’s tender recollection of his long lost friend, told mostly through images, highlights just what was lost. Luckily, we have Hujar’s gracefully emotive photographs as reminders.

Peter Hujar: John Erdman and Gary Schneider in Bed, 1986