In case you haven’t noticed, fashion from big corporate brands has become boring. The strategy of simplifying the garment, slapping a logo on it, and selling it to the masses, is now proving to be faulty as the masses increasingly question the value proposition.

But it’s not just fashion design that has suffered, so has the visual storytelling that goes with it. You’ve all seen the famous circa 2018 illustration of “blanding,” the practice of turning unique branding into the generic san-serif mush that has confused sterility with modernity. According to the art director set, fashion advertising has also been undergoing its own version of blanding as of late. The latest Substack rant on the topic comes from the author of an Instagram meme account, which is apparently our new critic class, went mini viral.

The rant offered the reasons for why fashion advertising sucks typical of an art director; brands don’t want to be creative anymore, they don’t know what they want, budgets are low, creative directors are dumb. But it doesn’t ask why such is the case. If you’ve ever talked to an art director, this simplistic story will sound familiar. Allow me to complicate matters.

In his 2013 book, Fashion Mythis: A Cultural Critique, the German cultural critic Roman Meinhold posited that all fashion advertising sells meta-goods, that is a collection of symbols that add intangible value to garments (and allows fashion to command hefty price premiums). One of the ways it works is that meta-goods are superimposed onto garments via ads. Usually, though not always, meta-goods feature in an ad’s background. Take your average Michael Kors ad, and you will most likely see a tall, young, white woman in front of a private plane, a helicopter, or a yacht. The meta-goods here are as obvious as Kors’s mall-bound clothes; buy Kors and you will be like the rich and idle. The ad holds a promise of traveling to glamorous locations, even if IRL your average Kors customer most likely travels from a parking lot of an outlet mall to their suburban home.

Meta-goods used to vary and played a big role in brand positioning. Tom Ford’s Gucci was all about getting laid. Versace was all about ridding the nouveau riche of shame associated with their lack of taste. Prada was about being quirky and vaguely intellectual. Ralph Lauren was all about that particularly straightforward line of American aspiration that Michael Kors swiped from him. However, what we are seeing today, in our confused post-modern society that can no longer imagine a future, is the erasure of meta-goods. A big part of it is that the consumer has become inured to or wary of traditional meta-goods, through attunement to the false promises of advertising and through change of mores. Take sex, for example. For decades “sex sells” has been one of the central tenets of advertising, especially in fashion. Today, this is no longer the case. Sex is seen as either too risky or too exploitative or kind of yucky. Add a bunch of such examples together and what you get is pure disorientation on the part of brands, which leads to flight to safety, which leads to blanding.

Contrary to what art directors believe, their clients are not dumb (dumb people don’t build multi-billion-dollar businesses); they are scared. Their fear is twofold: one is that sales are falling, and two is that they will be called out on social media for some real or perceived transgression. The first fear is a culmination of the decades-long drive to appeal to the biggest number of consumers possible. This constant averaging down is why their products now look indistinguishable, save for the logo, and therefore not desirable. The adage that if you stand for everything, you stand for nothing has permeated even the corners of the Internet that specializes in life-affirming (or death-affirming, depending on where you stand) messages of the “Live, Love, Laugh” variety and photos of sunsets on beaches and people in large hats. And if those people don’t want to buy your stuff, as a big brand you are dead. But what’s a corporate brand to do? Hitting the reverse gear risks alienating somebody, somewhere, and that is the one thing it cannot afford. This, and not the font type, is what keeps the executives up at night.

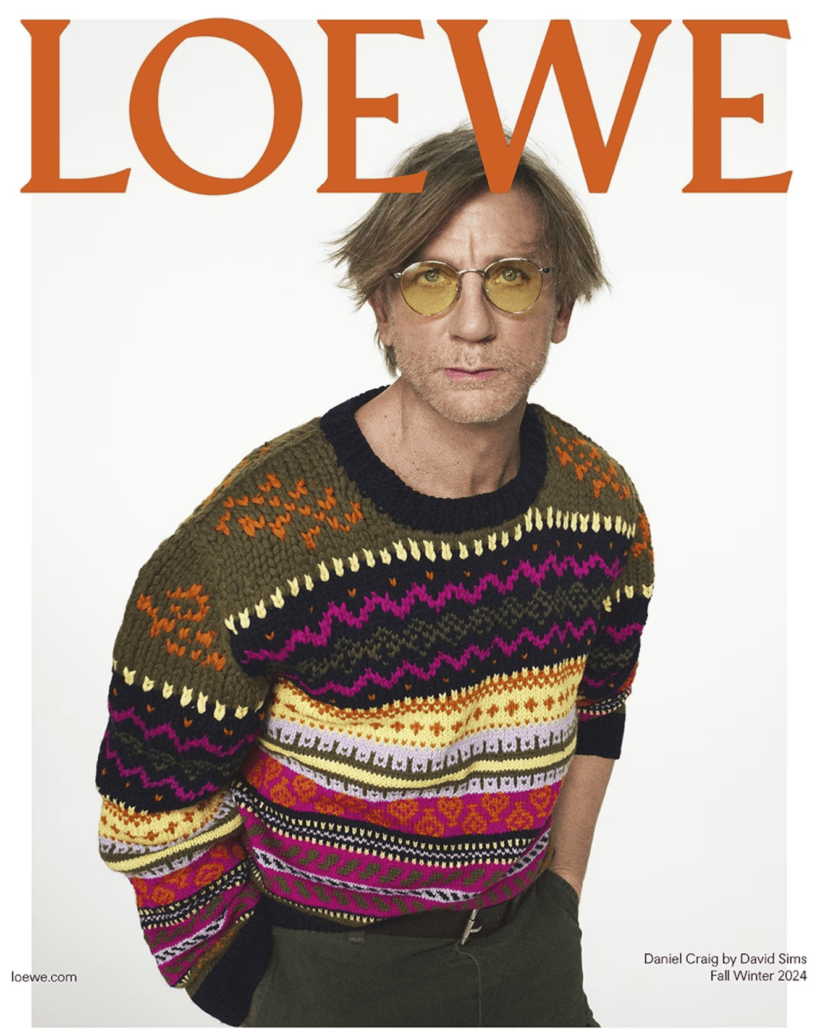

The second thing that drives advertising to blandness is the fear of a political misstep. Since the neoliberal West has decided that corporations are people and must therefore be in possession of morality (weird, but, Ok), it has been holding corporations to account in terms of political correctness. In recent years we have seen Prada, Gucci, and Balenciaga do the Internet walk of atonement with which the one Cersei did in The Game of Thrones pales in comparison. Brands are now in full and constant potential crisis management mode, which results in self-censorship. Like it or not, Balenciaga was the last brand with a clearly defined set of meta goods – a (fake) edge and meta-irony. That the brand would get burned, the way it did in a child-porn scandal, was only a matter of time. Look at Balenciaga’s post-scandal ads and you will see Kim Kardashian holding a bag in a room full of bags that is probably meant to signify one of the nine hundred walk-in closets she must own. The ad is as bland as they come, and what it shows are three last things that are thought to be foolproof: celebrity, logo, and product. Look at the latest Loewe campaign, and you see Daniel Craig (celebrity), wearing a sweater (product), and a huge Loewe logo on top. There is nothing in the background, no meta-goods. And that is increasingly where we are today. It’s not the budgets, it’s not lack of creativity, it’s the fact that today creativity is perceived to be potentially unprofitable, just like it is in film and art and music. Fashion is not that different, after all.

P.S. A couple of students from the StyleZeitgeist Academy course on the history of contemporary fashion provided some illuminating thoughts that informed parts of this article.